¿Cómo se moviliza a una sociedad para la guerra total en la era de TikTok? Si su modelo son las “milicias” cibernéticas que han surgido durante los últimos 15 meses de conflicto entre Rusia y Ucrania , lo hace reuniendo a las masas en las redes sociales para publicar memes propagandísticos y descargar scripts de hacking simples de aficionados.

WASHINGTON — How do you mobilize a society for total war in the age of TikTok? If your model is the cyber “militias” that have sprung up over the last 15 months of conflict between Russia and Ukraine, you do it by rallying the masses to post propaganda memes and download simple do-it-yourself hacking scripts.

A new study, due out Thursday from the thinktank CSIS and previewed exclusively by Breaking Defense, delves deep into the role that non-government groups have played in the ongoing cyber conflict. It grapples with how their role blurs traditional lines between civilian and non-combatant, neutrality and intervention, peace and war — and, most importantly, what effect they actually have.

Those actors include corporate giants like Microsoft, which, the study notes, has spent over $400 million since February 2022 to support Kyiv, primarily through free cybersecurity services and cloud hosting for Ukrainian agencies whose servers were threatened by Russian strikes. They include tech upstarts like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which rushed 500 Starlink satellite terminals to Ukraine in days, then later tried to roll back support when it realized Ukraine was using Starlink to target artillery.

But they also include a wide and wild array of loosely organized volunteers, who are the subject of arguably the most intriguing essay in the collection, by West Point professor Erica Lonergan.

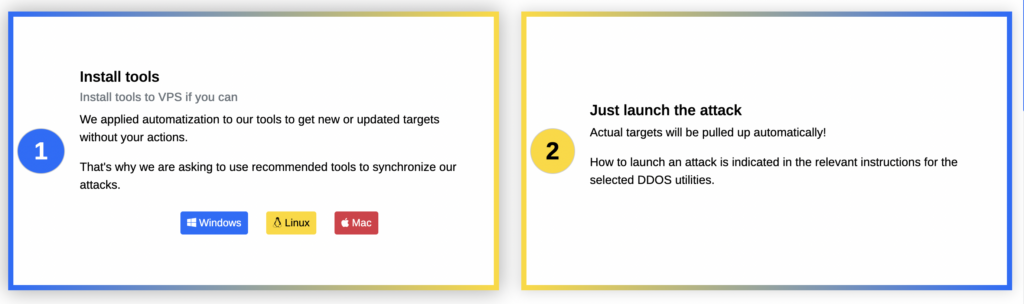

Consider the pro-Kremlin Killnet, described by Lonergan as “a modest hack-for-hire group” that started launching cyber attacks on Ukrainian and Western networks. “Killnet’s adherents are not particularly skilled and the group almost exclusively conducts straightforward DDoS [Digital Denial of Service] campaigns, publishing simple scripts on its social media channels for followers to use,” she says scathingly.

The group’s attack on US hospitals in February lasted just six minutes; a more impressive attack on Latvia managed to disrupt public broadcasting for half a day. Yet Killnet has parlayed its wartime activity into almost 2,000 claimed members (though how they’re counting is hardly clear), over 50,000 fans subscribed to its channels on Telegram, and its own line of merchandise, including, Lonergan writes, “a jewelry collaboration with Russian jeweler HooliganZ.”

Then there’s the self-proclaimed IT Army of Ukraine, which peaked at 400,000 claimed members from around the world and still has nearly 200,000. Officially independent of the government in Kyiv, the IT Army was the brainchild of the deputy prime minister, with backing from Ukrainian tech firms, and it may have a hard core of “Ukrainian defense and intelligence personnel,” Lonergan writes. What’s more, she says, “in March 2023, the Ukrainian government announced that it is in the process of developing legislation to formalize the IT Army and incorporate it into the country’s regular armed forces.”

Yet the largest impact of this “army,” Lonergan argues, has — like Killnet — been less tactical or economic than social and political. “The IT Army of Ukraine has leveraged social media to create both a local (Ukrainian) and international (largely Western) community of supporters aligned with its cause,” she writes. “The act of collectively conducting relatively simple cyberattacks thus builds and reinforces community, providing something around which to rally and energize supporters.”

CSIS scholar James Lewis agreed with Lonergan, saying in the report’s introduction she “makes the important point that while there is little evidence of effect from ‘hacktivism’ on opponent decision-making or military capabilities, there is strong evidence that the primary effect is political and international.” Such groups help “to build a community of support and to shape the narrative of the conflict for national and international audiences.”

In other words, a lot of the online “combat” is the 21st century equivalent of the great scrap drives in World War II. In both the US and Britain, governments rallied support for the war effort by encouraging otherwise uninvolved civilians, especially children, to donate potentially useful raw materials. Highly publicized campaigns scooped up everything from iron railings and old cannons, which could be melted down for warship hulls and weapons, to aluminum pots and rubber tires, which proved impractical to recycle and mostly sat in stockpiles unused.

But the materiel being gathered was never the point — or at least, not the primary point — of the wartime scrap drives. The most important purpose was to mobilize civilians who were otherwise uninvolved in the war effort. Gathering scrap helped give them a sense that they were doing something to help, to affect their fate, even win the war, instead of just suffering shortages, paying taxes, and hoping to not get bombed.

In the information age, metal matters less than data, and government propaganda less than social media. So it makes sense to mobilize the masses by getting them to click on things. One problem is that having civilians stage cyber attacks, even crude ones like Killnet’s, muddies their status as non-combatants in a way that scrap-metal drives do not.

“Ukraine’s cyber defense has relied on hundreds of thousands of IT volunteers who have supported cyber operations against the Russian state, but it is not clear to whether they are afforded any protection under international law,” writes Harvard fellow Julia Voo in her contribution to the study. “Interfering” with military electronics may legally count as “direct participation” in hostilities, she notes. What’s more, it is arguably illegal under US or British law for those countries’ civilians to hack Russian targets.

In theory, the distinctions are clear. “A proxy force that engages in ‘attacks’ at the behest of a state can be treated like a regular military force,” said Lewis, study’s editor, in an email exchange with Breaking Defense. “If they are doing it for gain, with no political motive, it’s a crime. You wouldn’t bomb criminals, but you would bomb guerrillas.”

In practice, “the lines can be blurry — some guerillas I worked with stole cows as a sideline — so the rule of thumb is whether there is a political motivation, a state sponsor, or state tolerance and encouragement,” Lewis said. “The degree of response is governed by proportionality, and we haven’t quite worked that out yet.” It’s one thing to bomb a country whose air force bombed you first, another to retaliate appropriately against a group that locked your computer files with ransomware, potentially without the knowledge of their government. And, as Lonergan notes, even if you do decide to bring pressure on a nation-state, it may not be able to stop a loosely organized group of citizens from hacking you.

There is great potential and daunting complexity for non-government groups to contribute to cyber war — and the CSIS study is raising crucial questions.

Fuente: https://breakingdefense.com