Esta publicación de la reconocida organización The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists analiza el estado actual y futuro posible, de las armas nucleares y las operaciones nucleares en Europa. Desde la anexión de Crimea por parte de Rusia en 2014 y la invasión de Ucrania en 2022, la retórica, las amenazas, las operaciones y las infraestructuras específicas de las armas nucleares han cambiado considerablemente y en muchos casos se han incrementado. Como lo muestra el informe, esta tendencia es completamente opuesta a los esfuerzos que desde hace más de dos décadas, se llevan adelante para tratar de reducir las cantidades, el poder destructivo y el rol de las armas nucleares en ese escenario y a nivel global.

Since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014 and invaded Ukraine in 2022, the rhetoric, prominence, operations, and infrastructures of nuclear weapons in Europe have changed considerably and, in many cases, increased. This trend is in sharp contrast with the two decades prior that—despite modernization programs—were dominated by efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

During this period, Russia has fielded several new nonstrategic nuclear weapons systems, increased military exercises, issued a long list of nuclear signals and threats, and upgraded its nuclear doctrine in a way that gives the impression that it has broadened the role of nuclear weapons and potentially lowered its nuclear threshold.

NATO, for its part, is also modernizing its nuclear forces and has further reacted by increasing its strategic bomber operations and nonstrategic nuclear posture, changing its strategic nuclear ballistic missile submarine operations, and talking more openly and assertively about the role and value of nuclear weapons.

Each side believes it has good reasons for beefing up the nuclear posture, but the combined effect is that the role and presence of nuclear weapons in Europe are increasing again after decades of efforts to curtail them. Unless the governments and parliaments of European countries increase efforts to halt this trend, the region is likely to descend further into growing nuclear weapons competition and posturing over the next decade.

In this Nuclear Notebook, we provide an overview with examples of how the nuclear postures in Europe are evolving, especially the infrastructures and operations. The overview is focused on nonstrategic nuclear weapons but also includes examples of how strategic nuclear forces are operated. The intention is to provide a factual resource for the public debate about the evolving role of nuclear weapons in Europe. As such, this notebook is not intended to be comprehensive but informative.

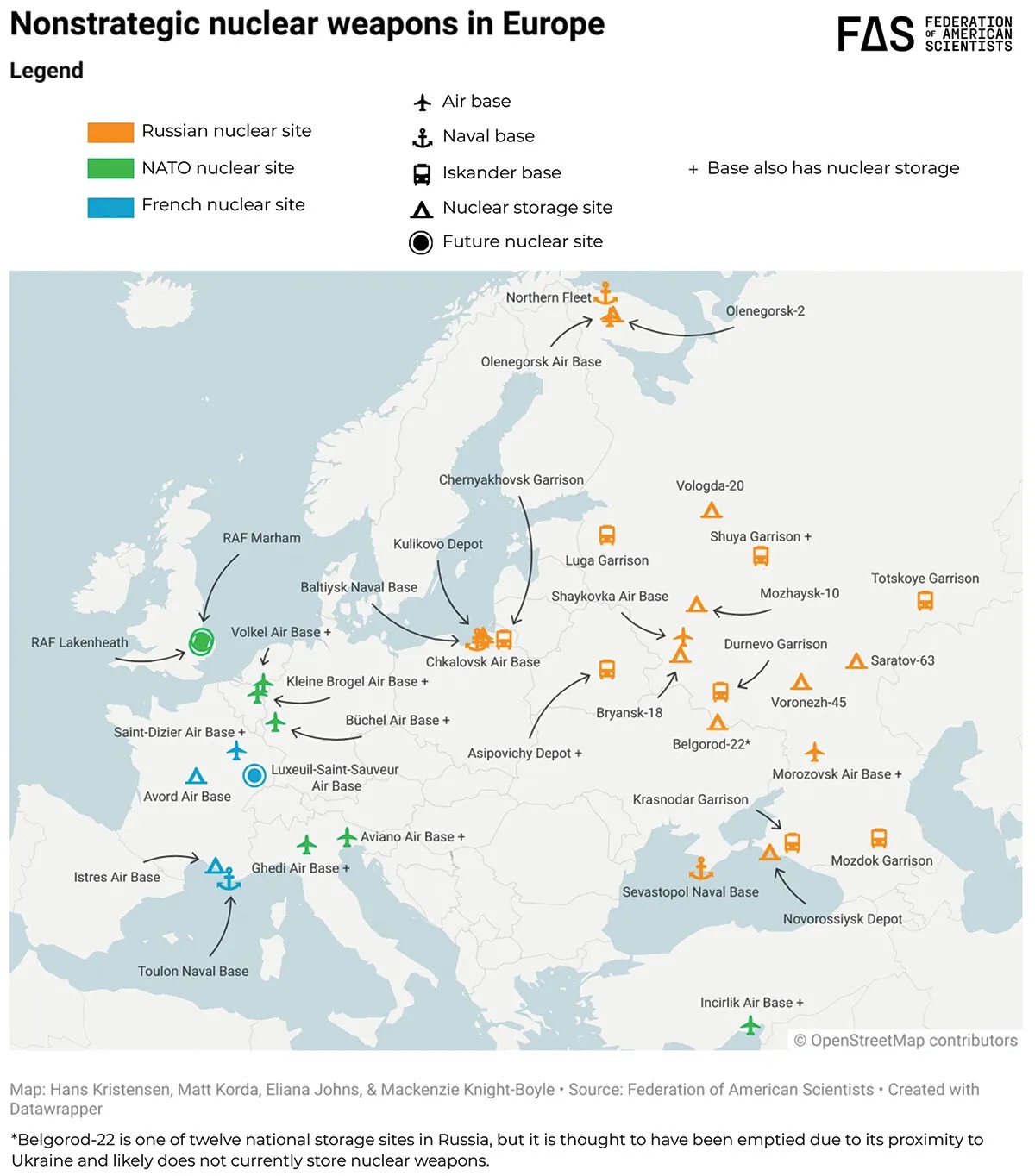

Nine countries currently operate nuclear forces in Europe: Belarus, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. The latter has announced plans to acquire nonstrategic nuclear weapons (see Figure 1), and a tenth country (Türkiye) hosts nuclear weapons on its territory.

Nuclear developments involving the Russian Federation

Since shortly before its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian officials have issued a wide range of signals and threats to use nuclear weapons if necessary (Mills 2024).[1] Russian officials had issued nuclear threats before (Kopiika 2024), but the concurrence of a major conventional war in Europe with increasing East-West military tensions and deteriorating political relations makes recent nuclear threats more worrying. Of particular concern is the role that nonstrategic nuclear weapons play because it may be this category of nuclear weapon that would be used first in a potential military escalation with NATO.

Russia’s nuclear posture has evolved significantly over the past decade. This is mainly due to Russia’s ongoing modernization of forces and infrastructure, growing military exercises before the Ukraine war, updates to its nuclear doctrine (although the specific effects are unclear), significant long-range bomber operations over European waters (probably constrained by the Ukraine war), as well as the unique three-phase exercises featuring nonstrategic nuclear weapons held in May, June, and July 2024.

The Russian military maintains a large stockpile of nuclear warheads for nonstrategic or shorter-range weapon systems (Kristensen et al. 2025a). The precise number is unknown, but the US Intelligence Community estimates it may include between 1,000 and 2,000 warheads for delivery by land, air, naval, air-defense, and missile defense forces (US Department of State 2024). During the Cold War, most Soviet nonstrategic warheads were deployed with the delivery systems at or near their bases, but since then, “Russia has consolidated its [nonstrategic nuclear weapons] into ‘centralized’ storage at fewer nuclear weapons storage sites … ” (US Department of State 2021). This includes about a dozen large national-level facilities where most, if not all, of the nonstrategic nuclear warheads are stored.

In addition, there are nearly three dozen storage sites located at military bases, roughly half of which are associated with strategic nuclear forces (Podvig and Serrat 2017). Of the base-level storage facilities associated with nonstrategic nuclear forces, about a dozen are located west of the Urals. Half of those appear to have been upgraded over the past decade, one has been added (at Morozovsk Air Base in the southern military district), and one has been inactivated (at Gatchina, south of Saint Petersburg).

Of the two base-level facilities in western Russia that have been upgraded, the most substantial is the forward storage facility near Kulikovo in the Kaliningrad Oblast. Since 2016, its underground bunker has been unearthed, refurbished, buried again, and the security perimeter has been strengthened. The outer security perimeter of the site and the main gate have also received upgrades (see Figure 2). As the only apparent nuclear warhead storage site in the Kaliningrad Oblast, the facility is probably intended to store nuclear warheads for all military services in the area. Whether nuclear warheads are currently present at the site is uncertain because of its forward location, and Russia has repeatedly stated that warheads for nonstrategic systems are kept in central storage, but they could quickly be shipped in during a crisis.

actical and long-range aviation

Most of Russia’s nonstrategic bomber bases do not include nuclear weapons storage facilities on-site. (Such facilities that existed during the Cold War were dismantled.) Instead, weapons are stored in central and regional storage sites and would be brought to the aircraft during a crisis, some via base-level storage facilities. Nonstrategic nuclear-capable aircraft in the region include the Soviet-era Tu-22M3 (Backfire) intermediate-range bomber and some of the remaining Su-24M Fencer-D fighter-bombers, as well as the new Su-34 (Fullback), MiG-31K (Foxhound) equipped with the Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile, and Su-57 (Felon).

Except for one fighter-bomber base in western Russia (the Su-34 base at Morozovsk in the southern military district), only the Tu-22M3 bomber bases appear to be equipped with designated nuclear weapons storage facilities. The Shaykovka air base in the Kaluga Oblast near Belarus has a nuclear weapons storage facility approximately four kilometers from the main base (see Figure 3). The bunker is about the same size as the Kaliningrad facility. Shaykovka air base was attacked by Ukrainian drones several times in 2023, and most of its Tu-22M3 bombers now appear to have been moved to other bases.

The second Tu-22M3 air base in western Russia—Soltsy Air Base south of Saint Petersburg—has a nuclear weapons storage site, but the base does not appear to have a permanent bomber unit and may function as a dispersal base. The third Tu-22M3 base at Olenegorsk on the Kola Peninsula has no nuclear weapons facility, but it is located only 17 kilometers from the large Olenegorsk-2 national-level nuclear weapons storage complex at Ramozero.

The only base for nonstrategic fighter-bombers in western Russia that appears to have an active nuclear weapons storage facility on the base itself is the Su-34 base at Morozovsk in the southern military district (see Figure 4). The storage facility was added sometime between 2005 and 2013. The base is only 130 kilometers from the Ukrainian border and was attacked by drones several times in 2024.

Iskander short-range missile launchers

The status and role of Russia’s short-range missile launchers have been the subjects of considerable debate for more than a decade. Russia promised in its unilateral Presidential Nuclear Initiatives from the early 1990s that all nuclear warheads for land-based nonstrategic forces would be eliminated. Many were indeed destroyed, but not all. Warheads were produced for the new Iskander short-range missile launcher, which can launch the dual-capable SS-26 (Iskander-M, 9K730) ballistic missile and the R-500 (SSC-7, 9M728) cruise missile, which might also be dual-capable. The Iskander replaced the old Tochka launcher and its dual-capable SS-21 (9M79) missile. The replacement was completed in 2019 at about 12 brigades and a training and integration brigade (see Table 1).

The interest in the Iskander focused on its improved military capability to launch quickly with more accurate missiles against high-value targets, as well as its forward deployment to bases close to NATO territory—most importantly, bases at Kaliningrad and Luga south of Saint Petersburg. Government officials and analysts have made numerous public claims that nuclear warheads for the Iskander system had been deployed to Kaliningrad, but the decade-long upgrade of the Kulikovo storage site (see Figure 2 above) indicates that it may not have contained nuclear warheads during that period. Even if the site doesn’t currently store nuclear warheads, the Russian military probably occasionally exercises procedures for bringing them in.

Despite the modernization from Tochka to Iskander being officially “complete,” the upgrades of the different Iskander bases vary considerably: Only five bases appear to have been completely modernized with a new launcher garrison and a missile depot; two new bases do not appear to have a missile depot; three new bases have launch units present but construction of the rest of the base has not progressed much; and two brigades are still based at older temporary bases because the new base facilities have not been completed.

Figure 5 shows satellite images of the different Iskander base completions.

Naval nuclear forces

The Russian Navy relies heavily on nuclear weapons and possesses weapons of all major categories: land-attack cruise missiles, anti-ship cruise missiles, air-defense missiles, anti-submarine rockets, torpedoes, gravity bombs and depth charges, and naval mines. Many of these weapon systems date back to the Soviet era and are being modernized or replaced with advanced conventional weapons. Some ships and submarines that used to have nuclear weapons missions are either retired or upgraded to conventional systems.

What remains is a smaller but more effective nonstrategic nuclear naval force. For example, the new Yasen-class attack submarine is being built in smaller numbers than the submarines it replaces and includes new weapon systems in place of some of the old. For the Russian Navy as a whole, one of the most important new weapons is the dual-capable Kalibr anti-ship and land-attack cruise missile. It has a longer range than many of the missiles it is replacing, a greater accuracy, and is being included in most new (and added to some old) ship and submarine designs (see Figure 6). From the North, Baltic, and Black Sea fleet areas, the Kalibr can potentially reach targets in almost all of Europe.

The Kalibr cruise missile probably features prominently in the US Intelligence Community’s estimate and projection for Russian nonstrategic nuclear weapons. Deploying a nuclear weapon system on a vessel requires special equipment and personnel, so it is reasonable to assume that not all dual-capable Kalibr-equipped vessels may be assigned the nuclear version.

Nuclear exercises

Russian nonstrategic nuclear forces are exercised at several levels. One involves on-base inspections, another includes regular range exercises with live or simulated firings of missiles or dropping of bombs, and a third level involves units participating in large-scale joint exercises such as the annual Zapad (West). Up until the Ukraine war, military exercises increased in size, particularly the Zapad exercises, which have included simulated employment of nonstrategic and strategic nuclear forces. The Ukraine war has caused the Russian military to move many units from their normal locations to the front line, and large exercises such as Zapad, which most recently took place in Belarus in September 2025, have decreased in size.

Nuclear-capable bombers occasionally carry out patrols over European waters. Mostly, these patrols are routine training operations, but they of course also serve as reminders of Russian capabilities to conduct long-range strikes with nuclear air-launched cruise missiles. Occasionally, the bombers will carry out what appear to be simulated nuclear attacks. For example, in March 2013, two Tu-22M3 bombers from the Shaykovka air base flew over the Baltic Sea and apparently carried out a simulated nuclear attack against Sweden (The Local 2013), a report later corroborated by NATO (2016).

Despite Russia’s numerous nuclear signals and threats (and occasional provocative events), changes to actual nuclear operations appear to have been less dramatic. When asked about Russian nuclear rhetoric, US officials have on several occasions said that they have seen few changes “on the ground” in the way Russia operates its nuclear forces.

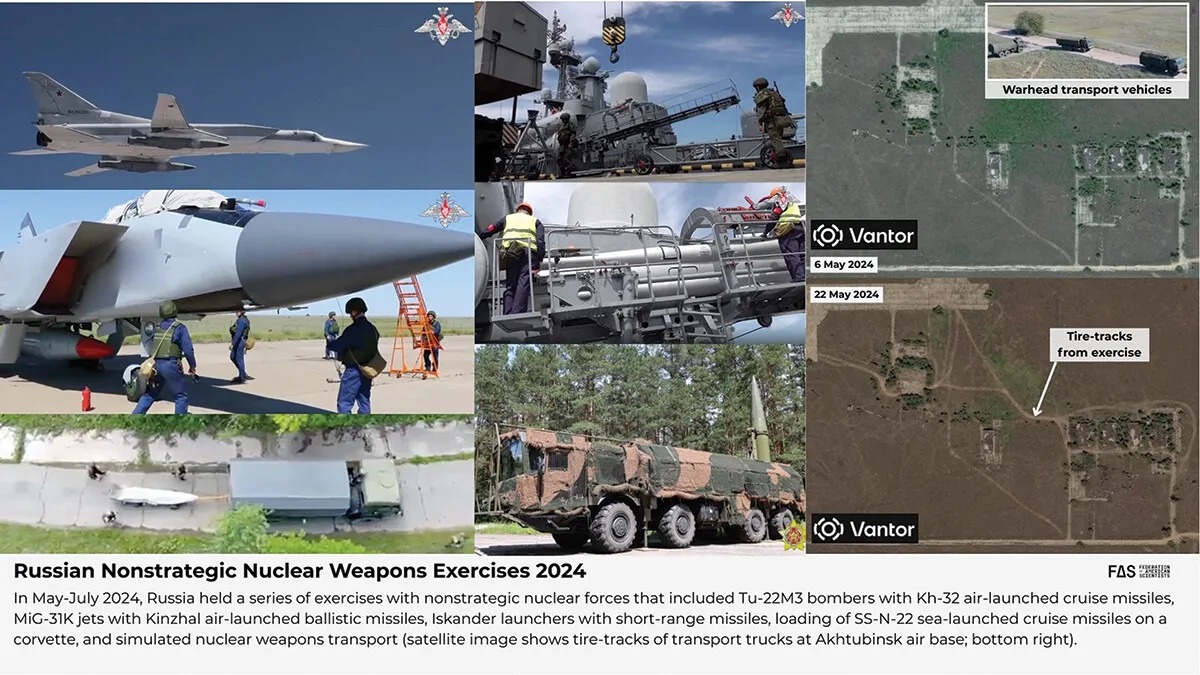

That changed in 2024, when the Russian military announced a series of exercises involving dual-capable nonstrategic nuclear forces. In explaining the basis for deciding to conduct the exercises, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs listed a plethora of grievances, including Russia’s opposition to the West supplying Ukraine with long-range missiles (Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2024). The exercises unfolded in three prominently televised phases in May, June, and July that involved Iskander launchers, joint operations with Belarus, Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers with Kh-32 missiles, MiG-31Ks with Kinzhal missiles, loading of an SS-N-22 sea-launched cruise missile on a corvette in the Baltic Fleet, as well as simulated nuclear warhead transports (see Figure 7). While Russia has invited Western observers to part of the Zapad exercises, it did not appear to do so with the nonstrategic exercises in 2024.

Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus

Since late 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko have advanced their shared goal of forward-deploying Russian nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory. While Russia has provided Belarus with nuclear-capable launchers and built support facilities, it is still unclear if nuclear warheads for these launchers are also present in Belarus. If so, this would constitute the first instance of Russia deploying nuclear weapons outside its borders since the end of the Cold War.

The arrangement, which appears to be similar to NATO’s so-called nuclear sharing arrangement, involves Russia supplying Belarus with dual-capable launchers for nuclear weapons: Iskander short-range ballistic missiles and bombs for Su-25 fighter-bombers. There is strong evidence that Russia is nearing completion of a nuclear warhead storage site near Asipovichy in central Belarus (Kristensen and Korda 2023; Kristensen and Korda 2024).

The arrangement, which has been justified by the two countries as a means of defending against a military threat from NATO, is thought to involve Russian control of the nuclear warheads. It is still unclear whether Russia has already shipped nuclear warheads to Belarus or if they are intended to be shipped in a crisis.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive timeline accounting for Russian and Belarusian actions related to Russia’s forward deployment of nuclear weapons.

Asipovichy depot

A military depot near Asipovichy in central Belarus is currently the most likely candidate for the storage of Russian nuclear weapons (Kristensen and Korda 2024). In addition to the depot’s identification in a leaked CIA document and the reported on-site presence of radiation detection equipment and iodine prophylaxis (a medical supplement used to mitigate radioactivity-related illnesses) (Shauliuha and Furlong 2025), satellite imagery indicates significant upgrades to the facility consistent with the possible storage of nuclear weapons (see Figure 8).

In the spring of 2023, land clearing began within the northern area of the depot to make room for multiple layers of new interior security fencing. Trees within the new inner perimeter were cleared approximately 20 meters away from the fencing, with evidence of additional digging for the likely laying of cables and sensors.

In addition, satellite imagery shows the construction of multiple new facilities within and alongside the new interior fencing, likely serving as additional security checkpoints, as well as a new command and control communications antenna.

A small parking and storage area is in the process of being converted into a new rail station, which would be consistent with Russia’s typical practice of transporting nuclear weapons by rail. The new rail station is being connected to an existing rail line that runs directly northwest of the depot.

Additional support facilities have also been constructed outside the northern area of the complex, as well as large mounts for what appears to be an air-defense system. In addition, garages for Iskander launchers have been completed at the Asipovichy garrison, approximately 10 kilometers west of the depot.

Nuclear developments involving NATO

NATO’s nuclear posture is undergoing significant changes, in large part in reaction to deteriorating relations with Russia. After decades of reductions, the number of nuclear weapons, the infrastructure for them, and operations are increasing again in Europe. Along with the physical changes come modifications of rhetoric; officials speak more explicitly about the importance and role of nuclear weapons than at any point since the end of the Cold War. Some European officials are now even advocating for more nuclear weapons.

The US Air Force currently deploys an estimated 100 to 120 nonstrategic B61-12 gravity bombs in Europe (Kristensen et al. 2025b). The weapons have for years been stored at six bases in five NATO countries: Aviano and Ghedi in Italy, Incirlik in Türkiye, Kleine Brogel in Belgium, Volkel in the Netherlands, and Büchel in Germany (Kristensen 2005). These US weapons are stored under a so-called nuclear sharing arrangement where dual-capable aircraft from those NATO countries are equipped and certified to deliver US nuclear weapons. National bases in Türkiye and Greece were also equipped with nuclear weapons storage vaults, but the weapons have been withdrawn, and the vaults are in caretaker status. Turkish and Greek dual-capable F-16s today serve only a contingency nuclear role.

There are indications that nuclear bombs may have recently been shipped to the U.S. Air Force base at Royal Air Force (RAF) Lakenheath (52.40816 °N, 0.55868 °E) in the United Kingdom (Burt 2025), which has undergone a significant upgrade to reactivate a nuclear mission (Johns and Kristensen 2025). The status of weapons at the base remains uncertain because of the unfinished construction of the infrastructure required for the nuclear mission. If weapons have indeed been deployed, the number of US nuclear weapons in Europe might now be around 120.

Moreover, the United Kingdom recently announced plans to buy dual-capable F-35A jets from the United States and join the nuclear sharing arrangement. The aircraft will be based at RAF Marham air base (52.6461, 0.5524), about 30 kilometers north of RAF Lakenheath (Yorke and Dunn 2025), presumably along with US B61-12 nuclear bombs, from the mid-2030s.

The addition of these two nuclear bases stands in contrast to recent statements made by NATO officials that the alliance did not need to deploy nuclear weapons at additional locations. Then-NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said in 2021 that there were “no plans of stationing any nuclear weapons in any other countries” (Bendeich 2021)—a statement echoed in 2023 by then-NATO nuclear policy chief Jessica Cox, who said that “there is no need to change where they are placed” (Kervinen 2023).

The nuclear upgrade of RAF Lakenheath and addition of RAF Marham are the latest developments in a broad modernization of nuclear bases, dual-capable aircraft, nuclear weapons, operations and exercises, as well as plans and policies in NATO. Some of these upgrades were already ongoing before Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 (when it annexed Crimea), whereas others have been added since, and more are expected to come. In addition to $385 million previously approved to upgrade storage sites, enhancing security measures, communication systems, and facilities to meet stricter US nuclear surety standards, NATO in November 2024 added an additional initial $500 million investment to modernize NATO’s nuclear command, control, and consultation (NC3) systems (US Department of Defense 2025).

The United States recently completed the production and deployment of the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb, an enhanced version of the legacy B61 bombs previously deployed in Europe. In addition to integration on the B-2 and the future B-21 strategic bombers, the B61-12 bomb has been integrated on US and allied-operated dual-capable tactical aircraft (DCA), including the F-15E, the F-16C/D, the F-16MLU, the PA-200 Tornado, and the F-35A. Except for Türkiye, every NATO country involved in the nuclear-sharing mission is purchasing the F-35A to serve in the nuclear strike role, including the United Kingdom. This modernization requires extensive upgrades to the bases, including the underground weapons storage vaults, underground cables, as well as nuclear command and control systems, security perimeters, and new facilities needed to service the more complex F-35As. Many of these upgrades are visible on satellite images (see Figure 9) and are described below.

Kleine Brogel Air Base, Belgium

Kleine Brogel Air Base (51.1685, 5.4666) in Belgium hosts approximately 10 to 15 US B61-12 nuclear bombs for delivery by Belgian F-16MLU aircraft. The base is expected to receive its first batch of F-35As in 2027. Kleine Brogel has a total of 11 protective aircraft shelters (PAS) equipped with a Weapons Storage and Security System (WS3), which includes an underground elevator-drive vault, as well as the associated command, control, and communications consoles and software needed to secure and unlock the weapons. Each vault can hold up to four bombs, for a maximum base capacity of 44 weapons, but is normally thought to hold one or two bombs each.

In recent years, upgrades have been completed, including a large loading pad for C-17A nuclear transport aircraft that has been added next to the suspected nuclear weapons area, the construction of a high-security facility has been completed, the upgrade of facilities of the US Air Force Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS) that controls and maintains the nuclear bombs, a new control tower, and upgrades to the underground cables and the Alarm Communication & Display (AC&D) system. Satellite images show significant construction in the center of the base of the support facilities needed for the new F-35A (see Figure 9 above).

Volkel Air Base, the Netherlands

Volkel Air Base (51.6577, 5.7016) hosts an estimated 10 to 15 US B61-12 US nuclear bombs for delivery by US-supplied F-35As. The new jet took over the nuclear strike role from the F-16MLU aircraft on June 1, 2024 (Netherlands Ministry of Defence 2024). There are 32 protective aircraft shelters at Volkel, 11 of which are equipped with WS3 vaults for nuclear weapons storage for a maximum base capacity of 44 weapons.

Recent construction at Volkel Air Base involves several new additions, including security-related construction upgrades similar to those at other nuclear weapons bases in Europe and a new loading pad surrounded by a high wall to conceal movements of weapons transported by the C-17A Globemaster III (the only US transport aircraft authorized to move the nuclear weapons). In addition, a high-security facility similar to the one added to Kleine Brogel has been completed, as well as the installation of new command, control, and communication cables.

Büchel Air Base, Germany

Büchel Air Base (50.1762, 7.0640) hosts an estimated 10 to 15 US B61-12 nuclear bombs for delivery by German PA-200 Tornado aircraft. The base is expected to receive its first F-35As in 2027. A total of 11 protective aircraft shelters at Büchel are equipped with WS3 vaults for nuclear weapons storage for a maximum base capacity of 44 weapons.

In the past few years, Büchel has undergone extensive modifications (see Figure 9 above), including a new service area for the F-35A, a refurbished runway, a loading pad for the US C-17A nuclear transport aircraft, upgrades of underground command, control, and communications cables, and an additional security perimeter around the aircraft shelters with nuclear weapons storage vaults, similar to those added to other nuclear weapons bases in Europe. During the base upgrades, the Tornado aircraft from the Tactical Air Wing 33 have been hosted at Nörvenich Air Base and Spangdahlem Air Base. The Federal Ministry of Defense of Germany recently requested an additional €644 million ($742 million) to fund infrastructure upgrades at Büchel, which would raise the cost of the project to an estimated €1.948 billion ($2.25 billion) (Kozatskyi 2025).

Aviano Air Base, Italy

Aviano Air Base (46.0313, 12.5968) hosts an estimated 20 to 30 US B61-12 nuclear bombs for delivery by US F-16C/D aircraft. The Aviano air base is home to the USAF 31st Fighter Wing with its two squadrons of nuclear-capable aircraft: the 510th “Buzzards” Fighter Squadron and the 555th “Triple Nickel” Fighter Squadron. Eighteen protective aircraft shelters at Aviano were equipped with underground vaults in 1996, but only 11 are estimated to be currently active for a maximum base capacity of 44 weapons. A significant upgrade of the area with the active nuclear weapons shelters, including a new security perimeter, was completed in 2014 and 2015 (Kristensen 2015). Aviano has not yet been listed for upgrade to the F-35A.

Ghedi Air Base, Italy

Ghedi Air Base (45.4319, 10.2670) hosts an estimated 10 to 15 US B61-12 nuclear bombs for delivery by Italian PA-200 Tornado aircraft. There are 22 protective aircraft shelters at Ghedi, divided into two groups of 11 on the northwestern and southeastern ends of the airfield.

New nuclear-related upgrades and new construction at the base are extensive (see Figure 9 above), including a new double-fenced high-security perimeter around eight of the northwestern shelters, upgraded security perimeters around the former alert area at the southern end of the base, new nuclear weapons maintenance buildings inside the northwestern nuclear weapons area and the southern former alert area, a new drive-through support building for nuclear weapons maintenance trucks at the USAF 704th MUNSS area, as well as a new loading pad for C-17A transport aircraft just outside the nuclear weapons storage area.

There is also significant ongoing construction in the center of the base that includes new shelters and support facilities for Italy’s incoming F-35A aircraft.

Incirlik Air Base, Türkiye

Incirlik Air Base (37.0025, 35.4267) hosts an estimated 20 to 30 US B61-12 nuclear bombs for delivery by US aircraft—a significant reduction from the 90 bombs that were stored at the base in 2000. However, unlike at other European bases, Türkiye does not allow the United States to permanently base its fighter-bombers at Incirlik. As a result, US aircraft would have to fly in during a crisis to pick up the weapons, or the weapons would have to be shipped to other locations before use.

In the late 1990s, WS3 underground weapons storage vaults were installed inside 33 protective aircraft shelters at the base. In 2015, a new security perimeter was added around 21 of those shelters (Kristensen 2015), suggesting that these are currently active. Despite reports that the Pentagon has previously reviewed plans for removing US nuclear weapons from Türkiye due to security concerns (Sanger 2019), the nuclear mission was heavily implied to still be in effect at Incirlik Air Base as recently as July 2023, when senior leaders from the US Air Forces in Europe’s “A10” Office of Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration visited Incirlik to discuss the “surety mission” and “the role that Incirlik plays in strategic deterrence” (Myricks 2023).

The United Kingdom

After the Cold War, the United Kingdom eliminated all its nonstrategic nuclear weapons, making it the first nuclear-armed state to do so and reducing its arsenal to a single platform: nuclear ballistic missile submarines. In addition, the United Kingdom began a gradual reduction of the number of nuclear weapons in its stockpile and those operationally available on the submarines (Kristensen et al. 2024).

The deteriorating security environment since the 2010s has triggered several changes to the United Kingdom’s nuclear posture. This includes decisions to increase the upper limit of its nuclear warhead stockpile and reestablish a nuclear fighter mission at RAF Marham.

The Integrated Defence Review in 2021 decided to reverse decades of UK gradual disarmament policies and announced an increase in the upper limit of the United Kingdom’s nuclear inventory, from no more than 225 warheads to up to “no more than 260 warheads.” The decision to increase was made in response to “the evolving security environment, including the developing range of technological and doctrinal threats” (HM Government 2021).

In addition, in June 2025, the UK government announced that it would buy at least 12 dual-capable F-35A fighters from the United States, join the NATO nuclear sharing mission, and base the aircraft at RAF Marham (UK Ministry of Defence 2025). RAF Marham was apparently chosen because it used to store US nuclear weapons, and 24 WS3 underground storage vaults were installed there in the late 1990s.

The government said the decision to reestablish an air-based nuclear capability “represents the biggest strengthening of the UK’s nuclear posture in a generation.” Although he didn’t explicitly mention Russia, UK Defence Secretary John Healey said that “we face new nuclear risks, with other states increasing, modernising and diversifying their nuclear arsenals” (HM Government 2025).

The decision was built on the Integrated Defence Review’s recommendation that the United Kingdom seek capabilities for “full spectrum” escalation management, and “commence discussions with the United States and NATO on the potential benefits and feasibility of enhanced UK participation in NATO’s nuclear mission” (HM Government 2025, 20).

RAF Marham will have to undergo significant upgrades to be able to house the F-35As and B61-12 nuclear bombs and might take about a decade to become fully operational.

France

Like the United Kingdom, France announced in 2025 that it intends to increase its air-delivered nuclear capability. During a visit to the Luxeuil-Saint-Sauveur air base (Air Base 116) in eastern France on March 18, President Emmanuel Macron announced plans to reactivate the base’s nuclear mission with the introduction of two squadrons of Rafale aircraft by 2035. Luxeuil lost its nuclear mission in 2011 when the EC 2/4 squadron was moved to Istres air base (Kristensen et al. 2025c). The reactivation of the nuclear mission at Luxeuil is part of a €1.5 billion ($1.7 billion) modernization plan, and the base will become the first to receive the next-generation Rafale F5 and the future hypersonic nuclear missile (MAF 2025; Vincent 2025) Élysée 2025). Once complete, this project will double the number of France’s nuclear-capable Rafale aircraft; it remains to be seen if it will also double the number of nuclear weapons available for them.

The decision to reactivate the nuclear mission at Luxeuil comes in response to the deteriorating relations and growing tension in Europe. There are no indications that France seeks to take over the US nuclear sharing role in Europe, but recent French statements and actions indicate a renewed consideration of the country’s nuclear role in Europe. In March, after German Chancellor-in-waiting Friedrich Merz said he wanted to discuss a nuclear sharing arrangement with the United Kingdom and France, French President Macron stated that he would “open the strategic debate on the protection of our allies on the European continent by our (nuclear) deterrent” (Corbet 2025; Rinke and Eckert 2025).

In April 2025, French Rafale aircraft—including Rafale from the nuclear base at Saint Dizier—deployed to Sweden for its annual Pégase exercise (Satam 2025). The deployment was significant not only because it included nuclear-capable aircraft, but it was also the first time that the annual exercise had taken place in Europe rather than in the Indo-Pacific. During the deployment, France’s ambassador to Sweden stated: “As President Macron has said, it is of course the case that our French vital interests also include the interests of our allies. In that perspective, the nuclear umbrella also applies to our allies, and of course, Sweden is among them” (Granlund 2025). The ambassador’s statement, however, has not been repeated by other French officials or formally confirmed in French declaratory policy. Although France is a member of NATO, its nuclear forces are not part of the alliance’s integrated military command structure.

NATO operations and exercises

Operations of NATO nuclear-capable forces in Europe have changed significantly over the past decade in response to Russia’s modernization and deteriorating relations with NATO. This is the case for the annual Steadfast Noon nonstrategic nuclear exercise involving dual-capable aircraft, for operations by US strategic bombers in support of NATO, and operations with strategic nuclear ballistic missile submarines in the region. Although NATO does not officially refer to these operations and promotions of them as nuclear threats, they are clearly signals or warnings to Russia about the capabilities it could face in response to aggression against NATO. Overall, while Russia has significantly escalated its nuclear rhetoric after 2014, NATO appears to have changed its nuclear operations more.

Signaling with nonstrategic fighter exercises

For many years, the Alliance has held an annual exercise for its dual-capable aircraft, but NATO has recently made the exercise more visible by declassifying its name: Steadfast Noon. This enables officials to more publicly promote the exercise and signal to potential adversaries. Moreover, with the expansion of NATO, more non-nuclear member countries are actively contributing to Steadfast Noon by providing conventional aircraft and other capabilities to support the nuclear strike mission overall.

The Steadfast Noon exercise normally lasts about two weeks, takes place in the fall, and is hosted by a different NATO member state each year. The 2024 iteration of the exercise was co-hosted by Belgium and the Netherlands, involved 13 countries and more than 60 aircraft, a slight increase from the previous year, which included “up to 60” aircraft (Kristensen 2024a; NATO 2024). Finland apparently participated in the nuclear exercise just 18 months after becoming a member of NATO (Kristensen 2024a). Norway also notably announced its participation in the exercise for the first time, having only attended as an observer the year prior (Paust 2024).

The most recent iteration of Steadfast Noon took place in October and appears to have been the largest so far, with 71 aircraft from 14 countries, with operations from the territories of four countries around the North Sea (Cook 2025; NATO 2025). The exercise was noteworthy because it was the first time ever that all the Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) sent conventional fighter-jets to support the nuclear strike training.

The increased official profile of Steadfast Noon is part of a heightened level of nuclear signaling to Russia. A video released by NATO about the exercise in 2024 explicitly referenced “Russia’s continued rhetoric on nuclear weapons” as “something that we keep a close eye on” (NATO Joint Force Command 2024). Another promotional video from NATO stated that the exercise practiced NATO forces against “a fictitious red adversary” (emphasis added) (SHAPE 2024). In a NATO video promoting the 2025 exercise, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte explained that the exercise “sends a clear signal to any potential adversary that we will and can protect and defend all Allies against all threats” (NATO News 2025).

Signaling with strategic bombers

The operations of US strategic bombers were among the first nuclear reactions to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Only three months after Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea in March 2014, the US Air Force sent two B-2 and three B-52 bombers to RAF Fairford in the United Kingdom for two weeks of operations over Europe (Mathis 2014).

The following year, the Commander of US Air Forces Europe informed Congress that in response to Russia’s bellicose behavior, “EUCOM has forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence missions to NATO regional exercises” (Breedlove 2015, 24).

Five weeks later, in April 2014, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers took off from their bases in the United States on Operation Polar Growl and flew directly to potential cruise missile launch areas over Arctic and northern European waters and back to the United States. A similar but larger bomber exercise (Operation Polar Roar) followed in 2016. The last time US bombers had conducted similar operations was back in 1987 during the Cold War (Kristensen 2016).

Since then, the bomber operations have continued to increase in frequency, areas of operation, and forward bases used. Some of the more noteworthy operations include: a record of six B-52 bombers flying over the North Pole toward Norway and the United Kingdom in August 2020; later that same month, a B-52 operating over the Black Sea is harassed by a Russian fighter crossing within only 30 meters in front of the bomber; in September 2020, two B-52s conducting operations over eastern Ukraine between Russia and Crimea; in March 2023, a B-52 flying over the Bay of Finland toward Saint Petersburg almost up to Russian air space before turning sharply south over the Baltic States; and in November 2024, a NATO video showed a B-52 flew east of Svalbard from the United States, straight toward the Kola peninsula, and down over Finland along the Russian border, on its way to join three other B-52s at RAF Fairford in southern England.

Moreover, with Finland and Sweden joining NATO in 2023 and 2024, respectively, strategic bombers now regularly use their airspace—something bombers never did a decade ago.

Signaling with SSBNs

A significant nuclear development in recent years has been the decision to send US ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) to European ports and surface for photo-ops. Before Russia invaded Crimea, US SSBNs rarely visited foreign ports (Kristensen 2024b). Since 2015, however, the submarines have made 10 public appearances in European ports and waters, often coinciding with operations by US E-6B TACAMO aircraft, which provide nuclear command, control, and communications.

In July 2023, a public reminder to Russia about nuclear missile submarines supporting NATO, the Commander of US European Command (2023) (EUCOM) flew onboard the USS Tennessee (SSBN-734) off the northwest coast of the United Kingdom before the submarine arrived at Faslane in Scotland. “Strategic deterrence provided by the USS Tennessee reflects the United States’ commitment to the Alliance,” he said, and EUCOM said the purpose of his visit was to “underscore US commitment to its Allies and support the combatant commander’s assurance and deterrence campaign objectives.” The nuclear weapons on the submarine, the commander explained, are critical to our integrated deterrence strategy” (US European Command 2023).

Moreover, in an unprecedented public forward nuclear signaling event, a US SSBN—the USS Tennessee—in June 2024 surfaced off the coast of Norway while an E-6B TACAMO nuclear command and control aircraft, that had forward-deployed to a Norwegian airfield shortly before, flew overhead for a highly publicized public relations event (US Naval Forces Europe 2024). Photographs published by the Norwegian Armed Forces showed Norwegian officials and military servicemembers posing with the Norwegian flag while standing on top of the submarine’s ballistic missile launch tubes (Nilsen 2024) (see Figure 10).

Research for this publication was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, the Jubitz Family Foundation, and individual donors.

Fuente: https://thebulletin.org